The Graduate Center, CUNY

While emotion is widely considered social, affect is often viewed as a preliminary, preconscious phenomenon. However, this distinction does not account for the diverse forms of affect. It is difficult to develop a vocabulary “to talk of the kind of judgments made by affect in that half second preceding conscious response: this is a kind of ‘thinking’ done by the body and not the mind” (Labanyi 224). In fairy tales, what interests me is not quite the preconscious response but the ways these preconscious bodily responses organize and make sense of the world. Still, I do not think the discourse in fairy tales is preconscious. Instead, I think these motifs of bodily responses might point to the ways in which subjectivities are formed through the kind of judgments that shape the kind of thinking done by the body. Spinoza’s category of affectio, a lasting impression that produces particular kinds of bodily responses, might be helpful if the interest lies in “this capacity of affect to be retained, to accumulate, to form disposition and thus shape subjectivities” (Watkins 269). While science allows for the study of these affects in the human body, at the fictional level of fairy tales these bodily responses are part of the compositional material with which agency is re-presented. This work is concerned with how motifs of affect mediating recognition outline the type of agency presented. Since the rise of the fairy tale coincides with the rise of the bourgeois public sphere (Zipes 40) 1, I consider appropriate to employ the theoretical framework of commodity and value to analyze recognition. I take recognition in the fairy tale to mean both identification of a lost subject (the heroine that went away) and the act of assigning a status or value to a subject or its opinions (the wisdom of the heroine). Different variants of fairy tales type AT 923 show that recognition in “The Goose Girl at the Spring” has passed from being mediated by one element of high use-value (salt) to another with high exchange-value (pearls). My analysis assumes that “values presuppose emotions to the extent that emotions provide the experiential basis for values” (Jaggar 56). I will consider the textual function of motifs vis-à-vis the social value of emotions in order analyze the motifs of affect that mediate recognition.

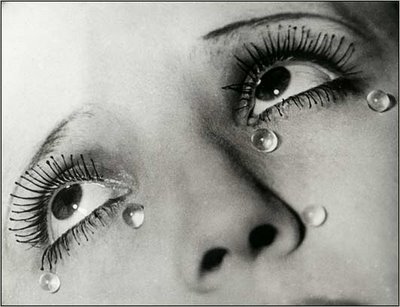

I am interested in one of the Grimm brothers’ fairy tales, “The Goose Girl at the Spring”2, because of the inclusion of a motif that is absent in all other tales cataloged by the Aarne–Thompson system as type 923. The Aarne–Thompson is a system for classifying folktales that uses motifs rather than actions to group the tales. In this type of folk tale, the king expels his youngest and prettiest daughter from his reign. The reason for the expulsion is that when asked how much she loved the king, she answered with some sort of analogy pertaining to salt as opposed to a more pretentious element. This response is in some variants taken as proof of a lack of love, and in others as proof of a lack of cleverness. In either case, the heroine is always expelled from the kingdom because of her heterodox sense of self in relation to the other that the king constitutes. Precisely because these fourteen 3 folk tales under type 923 are classified by the common motif of loving the salt and not according to what is done with it, it is that these differences stand out. In “The Goose Girl at the Spring”, sadness has exchange-value. That is to say, the heroine cries pearls. Tears solidify in order to bring recognition to the heroine with no need for ‘cooking’. Cooking, a motif present in all other tales classified as AT 923 4, is what eventually allows the maid to prove the king wrong about the importance of salt. In the case of the French and the Basque variants, the heroine does not work as a cook but as a shepherdess. However, recognition, in the sense of regaining noble status, is achieved by her cooking for the prince and placing a ring in the dough. Reprisal, on the other hand, is accomplished when at the wedding she orders that her father be served only bread without salt in order to prove him wrong. In the Grimms’ version, there is no such a thing as proving the king wrong, as the protagonist retires to a role of submissive resignation. “The Goose Girl at the Spring” is the only tale of this type in which recognition of the cast away heroine is not mediated by salt but by pearls. I refer to recognition both in the sense of rediscovery and understanding or acceptance.

“The Goose-Girl at the Spring” begins in a lonely place. A nobleman carries an old woman’s burden to her hut and is rewarded with an emerald box containing a pearl. When he gives the box to the heroine’s mother, the queen, she recognizes it as one of the pearls that her daughter used to cry. The queen and the king resolve to follow the count and seek out the old woman who gave the count that pearl. When the heroine reunites with her parents, the dynamic of the encounter is very different from all other folktales. The heroine prepares for the reunion through the house chore of sweeping rather than cooking. She does not know her parents are coming; consequently she cannot device any form of strategy or attitude. Moreover, at the moment of reunion, she does not go towards her parents. She waits patiently inside her room until the housekeeper tells her to come out. The moment she sees them, she throws herself on them, kissing them and weeping. Once the king realizes that he has no kingdom to give her in order for her to marry the count, the old woman offers her the treasure that the heroine had wept in those three years of sadness.

All but one of the fourteen tales that follow AT 923 present a plot that goes from rejection to reprisal to apology. The Grimms’ tale is the only one in which reprisal is absent. Generally, reprisal is enacted through cooking in the event of a wedding. In the English, French, Basque, Indian and Italian versions, the maid orders the cook not to use salt. In other Austrian and German versions, the maid learns to cook superbly and gains direct agency in the reprisal. These last two tales have three things in common with the Grimms’ account of this tale: the language, the time of publication and the act of crying included in the plot. In Zingerle’s tale “The Most Indispensable Thing”, the king has to appoint an heir to the throne, and needs to choose one of his three daughters. He asks his daughters to bring him a present that is most necessary in human life. The youngest daughter brings a pile of salt. As a result, the king gets angry. The rejected daughter goes into the unknown world. There, she learns to cook at an inn. Time goes on. Later, the king hears of the reputation of an excellent cook and hires her to cook at the oldest princess’ wedding. The youngest daughter, working as a cook, serves all the dishes excellently prepared, but makes sure that the king’s favorite dish is served without salt. The king complains, calls the cook and, without recognizing his youngest daughter, asks her why she forgot to salt his favorite dish. The youngest daughter then replies, “You drove away your youngest daughter because she thought that salt was so necessary. Perhaps you can now see that your child was not so wrong” (Ashliman n.a.). The king begs for forgiveness, and they live happy ever after.

In “The Goose Girl at the Spring”, the performance of tears causes the subject to apprehend a different conception of recognition while emphasizing the ancestry of the exotic object/princess. Tears as pearls convey a different schema of thought toward identity. In the “Epistemology of the Object,” E.L. McCallum asserts that, “the identity of the subject is not a fixed point of reference but an ongoing process of incorporating and performing oneself in relation to the objects and codes around one” (163). Differently from all other versions in which the princess engages with the new subject she becomes, the Grimm tale places the character in a state of latent subjectivity. Having deviated from the pleasing mandates of logic, she now corrects her behavior. The knowledgeable eloquent woman is substituted by a literary topos that fits better the trend of silent femininity in Germany during the mid-nineteenth century:

Evidence from diaries and letters suggests that by the 1830s, silence as a positive feminine attribute had gained wide acceptance in all social classes in the dukedoms, principalities, and free cities that made up the Germanies, and that the 1860s and 1870 marked the extreme point for the “silent woman” in Germany (Bottigheimer 116).

The other German-language tales of the same type were published in 1852 (“The Necessity of Salt”, Austria) and in 1856 (“The Most Indispensable Thing”, Germany), the Grimms’ tale 179 was published in 1857. The Bechstein’s version, “The Most Indispensable Thing”, published in 1856, ought to have been well known by the Grimms, since Bechstein was nineteenth century Germany’s most popular editor of fairy tales. Nevertheless, the Grimms chose another contemporary version of Austrian origin, circulated by Andrea Schumacher. They intended to render texts suitable for children, and that might have been the reason for this tale to be selected to educate children and young girls not to speak back at their parents. “The principle that children must keep quiet before speaking is one that surprises us today, but it should not be forgotten that some years ago, before the 1940 war at least, the child’s education basically began with an apprenticeship of silence” (Foucault 341). Combining the expectations about proper bourgeois femininity and teaching both genders not to defy their parents, the Grimms chose a source or version that fit these emotional roles. In Andrea Schumacher’s versions, the final motif of proving one’s father wrong was exchanged with the one in which silent suffering was rewarded with riches.

Sadness is present in all other tales, but it neither accrues a value nor it is a motif in the resolution of the story. Only in the Grimms’ tale, the act of crying performs in the narrative. In this fairy tale, the queen alludes to the girl’s performance of weeping three times in the story and refers to it as a quotidian act. I take performance here as the one that endorses the status of the heroine by its expression. Rather than an unusual episode in the story, weeping pearls is a behavior that constitutes the identity of the protagonist. Unlike the Grimms’ version, the Bechstein and Zingerle versions portray crying as transitory act, and not as a behavior. Although all these versions have in common the presence of the act of crying in the plot, in Bechstein and Zingerle the protagonist stops crying and moves towards agency:

With deep sorrow the rejected daughter went out into the unknown world, comforted only by her own good sense. …She found a female innkeeper, and entered as apprentice in the art of cooking (D. L. Zingerle, Austria). (Ashliman n. a.)

Crying, the youngest princess then turned away from her hard father, and walked far, far away from the court and the royal city…She came to an Inn and offered her services to the female innkeeper (D. L. Bechstein, Germany). (Ashliman n.a.)

How she cried when she was forced to leave us! The entire way was strewn with pearls that fell from her eyes. Soon after, the king regretted his severity […] (Grimm 566).

In the first two cases, she learns to cook and thereby acquires an independent profession. As the sophistication ceases, the tears go away. While crying as an expression of a sophisticated soul might be nowadays “philosophically dubious and historically outdated”, that was not the case in the nineteenth century (Elkins 95):

There was a time when cultivated audiences in Germany wept at concerts instead of clapping or shouting. Beethoven tells of giving a piano recital in Berlin and hearing no applause at the end; he turned to the audience and saw people waving tear-stained handkerchiefs. The practice annoyed him, because it seemed Berliners were too finely educated. (The German phrase is fein gebildet, literally “well pictured”, as if their educations had made them into beautiful images). He wanted his audience to be challenged, uplifted, and inspired (Elkins 196).

The performative crying matches parameters of refinement and sensibility for the ‘finely educated’ class and women. Tales were to inspire respect and obedience, rather than to give uplifting ideas that nourish challenging behaviors.

Social value of emotions

In the History of Tears: sensibility and sentimentality in France, Anne Vincent-Buffault notes that it was common for people attending salons to tell stories that moved the audience to tears (9). It is possible that the Grimm brothers absorbed this culture of tears and stories in the very same settings in which stories were told and collected. “What is especially interesting is that an extensive range of Grimms’ tales—“Little Red Riding Hood”, “Sleeping Beauty”, “Cinderella”, the first part of “Hansel and Gretel”, “Cat-skin” and even the subsequently excluded “Bluebeard and Puss-in Boots”—have been handed over from Perrault and his collection in French to German bourgeois families who liked to converse in French at home” (Hagen, Rolf quoted in Scherf 81). Andrea Schumacher, who provided the tale “The Goose-Girl at the Well” to the Grimm brothers, is also the source for different variants of “Cinderella”5. For instance, “The Goose-Girl at the Spring” substitutes the shoe that is left behind for the souvenir of sensibility—a pearl that fits a specific person’s tears.

Nevertheless, tears were not only a sign of first natures but also an element of sensible trade. Vincent-Buffault’s research shows how tears mingled and mixed were given away and shared, elicited, paid for and bought: there were “tributes of tears,” “debts of tears,” and a whole liquid economy of love and friendship (viii, 17-18), a whole business of tears. Love was to be measured in a performance of sadness and sorrow:

Respect, love, or simply the feeling of being part of humanity invited everyone to keep an account of what had been expended. By making someone cry, a debt of tears was contracted (Buffault 17).

Andrea Schumacher and Wilhelm Grimm understood this ‘liquid economy’ too perfectly and adjusted the tears to pearls6. As pearls appeared, the tropes of cooking and reprisal were lost.

The maid in “The Goose-Girl at the Spring” does not shed tears. While crying quickly moves to agency and self-confidence in other versions, such as Bechstein’s and Zingerle’s, it metamorphoses into pearls in the Grimms’ tale. The main object of recognition in the tale, salt, is transformed into pearls, preventing the plot from moving forward into reprisal and agency. It is worthy noting the difference between the phonic obnoxiousness of a cry and the silent repose of a pearl produced under the surface. In “The Goose-Girl at the Spring”, sadness becomes solidified and is freed of agency. Like the act of speaking, the act of crying is beautified and deprived of use-value and transformed into pure exchange-value. Once the motif of crying pearls is introduced, the motif of the girl speaking back to her father (and proving him wrong) is absent. No reprisal is employed through salt because salt is now pearls:

So far no chemist has ever discovered exchange-value either in a pearl or a diamond. The economists who have discovered this chemical substance, […] find that the use-value of material objects belongs to them independently of their material properties, while their value, on the other hand, forms a part of them as objects. What confirms them in this view is the peculiar circumstance that the use-value of a thing is realized without exchange, i.e. in the direct relation between the thing and man, while, inversely, its value is realized only in exchange, i.e. in a social process (Marx 177).

Obviously, chemists don’t find exchange-value in pearls because exchange-value is social and not chemical. As commodities, tears hold no exchange-value, but pearls do. The Grimms’ tale substitutes a thing with a high use-value for another with a high exchange-value. Salt, which is in direct relation to ‘man’, is replaced by pearls which find its value in the social process. The woman’s voice surrogates the power that articulates emotion, producing a substitute value. In the majority of the tales following type 923, agency is exercised through the use of the object by its material (natural) properties in a direct relation between the girl and the salt. That is, the protagonist chooses to spend or retain the value of the salt. The salt is not her-self; she can use it or act by omission. Instead, the pearls are part of her-self, and she cannot help but cry them.

A study of the motifs of affect in “The Goose-Girl at the Spring” suggests that the emotions that are chosen to mediate experience reflect prevailing forms of life. Moreover, changes in mood, literary reading images and intertextual echoes of fragmentary themes might suggest that motifs of affect could reflect prevailing forms of emotional life. “In the fairy tale, ideological elements associated with free enterprise, wage labor, accumulation and profit are added, questioned and evaluated” (Zipes 41). The act of collecting tales carried by the Grimms intended to show that the Germans shared a similar culture. Other tales of this type encompassed the act of expressing a sense of self by means of a rare common sense. In “The Goose-Girl at the Spring”; notions of value coming from bourgeois taste refashioned behaviors that glitter silent resignation with an aura of magic. In order to preserve the ideal image of a virtuous and cultivated woman, the tale neglects the value of agency, self-assurance and independence that a profession entailed. The value of tears that the era attributed to high-class socialites, as well as the gender expectations of sensibility and silence towards women, conditioned the motif of affect mediating recognition in “The Goose Girl at the Spring”. The act of involuntary exposure of sensibilities (crying pearls) was privileged over an act of active omission (omitting salt) as a strategy for being understood. Emotions are simultaneously made possible and limited by the conceptual and linguistic resources of a society (Jaggar 54). We can see that the motifs of affect give form to different economies of recognition. One form of recognition underlines reunion and forgiveness; the other one underlines encounter and understanding. The motif of affect that mediates recognition outlines the type of agency because it sets the nature of the exchange.

Notes

1 Jack Zipes affirms that “the folk tale as a popular narrative and dramatic form which addressed the needs and dreams of the masses during feudalism was gradually appropriated and reutilized by bourgeois writers who sought to express the interests and conflicts of the rising middle classes during the early capitalist period” (40).

2 This Grimm’s tale was taken from Wiener Gesellschafter by Andrea Schumacher, Wien, 1833.

3 I am following here the selection done by the folklore researcher D.L. Ashliman. There is one Mexican variant presented by John Bierhorst in Latin American Folktales: Stories from Hispanic and Indian Traditions that Ashliman does not include. This version also includes reprisal in the form of omitting salt at the wedding banquet.

4 Tales belonging to ATU 923 include: “Cap o’ Rushes” (England), “Sugar and Salt” (England); “As Dear as Salt” (Germany); “The Necessity of Salt” (Austria), “The Most Indispensable Thing” (Germany); “Water and Salt” (Italy) and “The King and His Daughters” (India). Source: See Ashliman. “The Value of Salt” (Italy). Source: Tale variant 214 BUSK, Folklore of Rome. London, 1874. 403-406. “Salt and Water”. Source: Folk-Lore, Vol. III. (Issued quarterly).

5 See Roalfe Cox pages 84, 225, 275.

6 The motif of ‘crying pearls’ is not unknown, What I find of interest is the introduction or transposition of the motif into a type of tale that traditionally does not contain this motif in the plot. Note 30 in Roalfe Cox traces the motif of ‘crying pearls’ around the world folktales: The (pearl is made, in the myth, to spring oat of Venus’s tear. Eve’s tear, like Frigg’s tears, are pearls in water, nuggets of gold on land -Corpus Poet. Boreale, i, cvi). Wainamoinen’s tears are pearls (see Kalewala, Rune 22). So are the tears of the Chinese merman (see F. L. Journal, vii, 319). According to Sicilian popular tradition, the tears of unbaptised children turn to pearls when poured into the sea by the angel who has collected them (Pitre, F. L. /., vii, 326). In a tale from the foot of the Himalayas, published in Russian by Minaef (No. 33), a princess weeps pearls (she also laughs rubies, see note 51). Cf. Cavallius, p. 142; Chodzko, p. 315; Glinski, iii, 97; Karajich, No. 35; Stoke. 1, No. 2. (See Roalfe Cox, p. 495) Additionally, at least one “Cinderella” variant, “Grattula-Beddattula” (Fair Date) has an heroine that shakes pearls and jewels from her hair. 295 Pitre Fiabe novelle e racconti popolari Siciliani, vol. i. Story No. XLII, p. 368. (See Roalfe Cox 116n)

Bibliography

Ashliman, D. L. Love like Salt.Pittsburgh University, 1998-2011. Web. 6 Nov. 2011.

Bechstein, Ludwig. Neues Deutsches Märchenbuch. Leipzig & Pesth: Hartleben 1856. 171-75. Print.

Bierhorst, John. Latin American Folktales: Stories from Hispanic and Indian Traditions. New York: Pantheon Books, 2002. Print.

Bottigheimer, Ruth B. “Silenced Women in the Grimm’ Tales: The “Fit” Between Fairy Tales and Society in Their Historical Context in Fairy Tales and Society: Illusion, Allusion, and Paradigm. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. Print.

Elkins, James. Pictures and Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings.New York: Routledge, 2001. Print.

Foucault, Michel, Frédéric Gros, François Ewald, and Alessandro Fontana. The Hermeneutics of the Subject: Lectures at the Collège De France, 1981-1982. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2005. Print.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Translated by Jack Zipes. New York: Bantam Books, 1987. Print.

Jaggar, Alison M. “Love and Knowledge: Emotion in Feminist Epistemology” Emotions: A Cultural Studies Reader. Ed. in Harding, Jennifer, and E D. Pribram. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2009. 50-68. Print.

Kaplan, Fred. Sacred tears: sentimentality in Victorian literature Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987. Print.

Labanyi J. “Doing Things: Emotion, Affect, and Materiality.” J.Span.Cult.Stud.Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 11.3-4 (2010). 223-33. Print.

McCallum, E.L. “Coda”. Object Lessons: How to Do Things with Fetishism. New York: SUNY Press, 1999. Print.

Marx, Karl. Kapital. New York: Penguin Group, 1992. Print.

Roalfe Cox, Marian R. Cinderella: Three Hundred and Forty-Five Variants of Cinderella, Catskin, and Cap O’rushes. Whitefish: Kessinger Publ, 2007. Print.

Scherf, Walter. “Family Conflicts and Emancipation in Fairy Tales,” in Children’s Literature, Volume 3, 1974. 77-93.

Vincent-Buffault, Anne. The history of tears: sensibility and sentimentality in France. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

Watkins, Megan. “Desiring Recognition, Accumulating Affect” in The Affect Theory Reader. Ed. Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010. 269-285. Print.

Zingerle, Ingnaz and Joseph. Kinder und Hausmärchen: Tirols Volksdichtungen und Volkbräuche, vol. 1, no.31. Innsbruck: Verlag der Wagner’schen Buchhandlung, 1852. 189-191. Print .

Zipes, Jack. Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002. Print.

'AS TEARS GO BY: MOTIFS OF AFFECT IN FAIRY TALES' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!